Herpesviren - stille Begleiter oder schlechte Gesellschaft?

Herpesviren besitzen ein DNA-Genom von über 100 000 Basenpaaren mit einer Vielzahl an Genen und sind neben den Pockenviren die komplexesten Viren des Menschen.

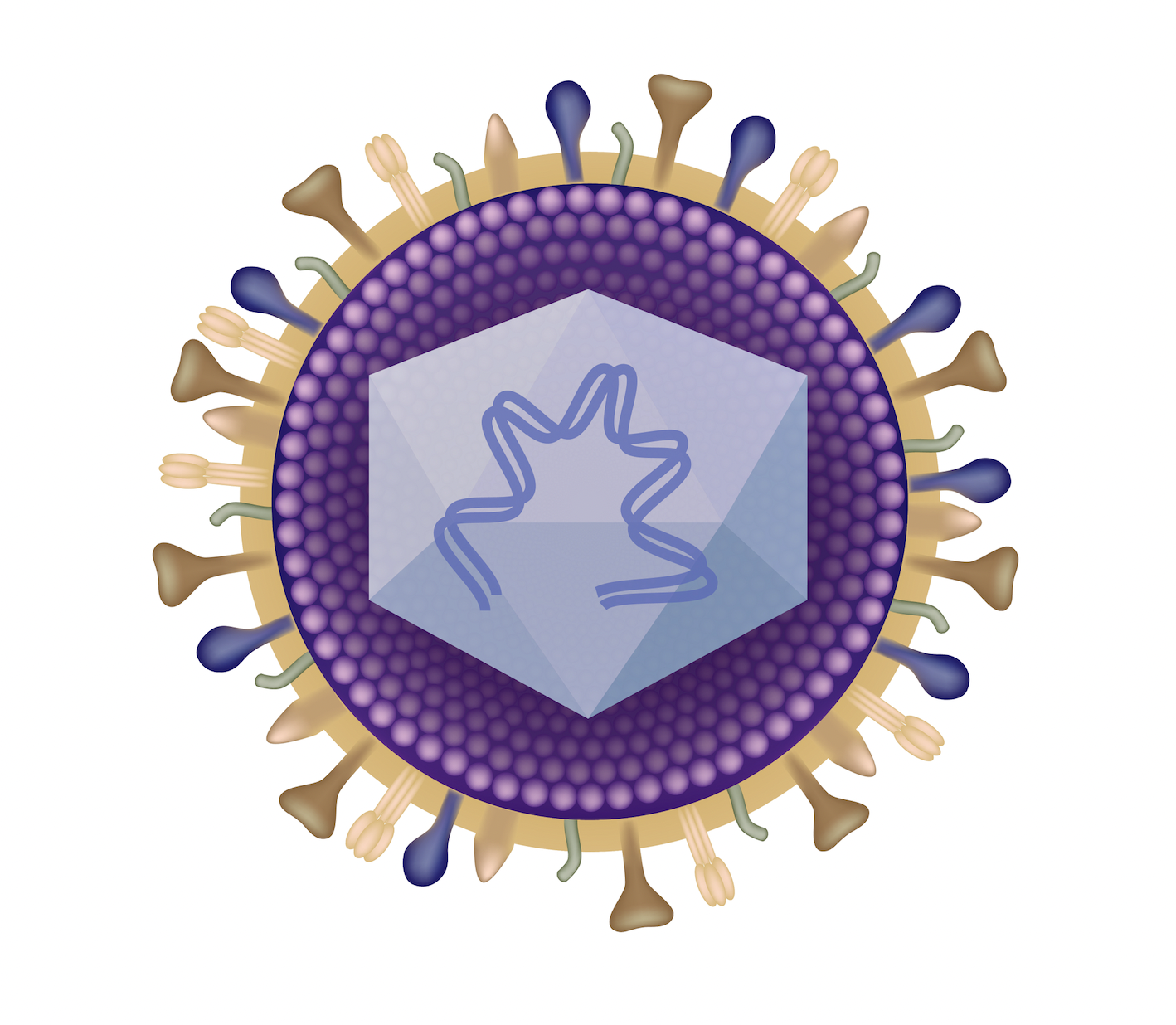

Abbildung 1: Schematische Darstellung des Herpes simplex Virus (Bildquelle Shutterstock #147789413)

Das spiegelt sich auch in ihrer Struktur wider: In der Virusmembran befinden sich zahlreiche Glykoproteine, die dem Virus vor allem zur Infektion verschiedener Zelltypen des Wirts dienen. Sie umhüllt eine sogenannte Tegumentschicht aus Proteinen, die das Virus bereits fertig synthetisiert mitführt, um die Wirtszelle bei Infektion sofort in die gewünschte Richtung zu beeinflussen. In das Tegument ist wiederum das Viruskapsid eingebettet, welches das Genom umschließt (Abb. 1). Herpesviren sind hochspezifisch an ihren Wirt angepasst.

Eine Besonderheit der Herpesviren ist, dass sie nach der Primärinfektion eine lebenslange Persistenz etablieren. Dies ist ihnen möglich, da sie in ausgewählten Zellen über lange Zeit, oft viele Jahre, nur einen kleinen Teil ihrer Gene exprimieren und keine Nachkommenviren produzieren. Diese latent infizierten Zellen werden nicht durch Virusreplikation zerstört und entgehen der Detektion durch das Immunsystem. Ausgelöst durch teilweise noch nicht verstandene Stimuli können die Herpesviren in diesen Reservoirs latent infizierter Zellen reaktivieren und wieder aktiv replizieren, was zur Ausscheidung infektiöser Viren und häufig auch zu klinischen Krankheitsbildern führen kann1.

Die folgenden menschlichen Herpesviren sind bekannt:

Fazit

Die humanen Herpesviren sind keineswegs harmlose Begleiter. Auch wenn praktisch jeder etwa ein halbes Dutzend von ihnen in sich trägt und in der Regel nichts davon bemerkt, so können sie im Alter, bei Schwächung des Immunsystems, oder auch - zumindest scheinbar - zufällig sowohl bei der Erstinfektion als auch bei der Reaktivierung zu schweren Erkrankungen führen. Das Beispiel des Varizella-zoster-Virus stimmt allerdings zuversichtlich, dass dies nicht so bleiben muss. Bei diesem Virus stehen mittlerweile sowohl gegen die Krankheit im Rahmen der Primärinfektion, die Varizellen, als auch gegen die Sekundärmanifestation, den Herpes zoster bei bereits infizierten Personen, Impfungen zur Verfügung. Selbst wenn es nicht gelingen sollte, vor der Primärinfektion zu schützen, so zeigt das Beispiel der Impfung gegen Herpes zoster, dass es prinzipiell möglich ist, das Immunsystem durch eine Impfung auch nach der Infektion so zu stärken, dass die gefährlichen Sekundärmanifestationen der Herpesviren größtenteils verhindert werden können. Es bleibt zu hoffen, dass dies für weitere Mitglieder dieser Virusfamilie gelingen könnte.

Referenzen

1. Pellett, P.E. and B. Roizman, The Family Herpesviridae: A Brief Introduction, in Fields Virology, P.M.H. David M. Knipe, Editor. 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

2. Rabenau, H., et al., Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus types 1 and type 2 in the Frankfurt am Main area, Germany. Medical Microbiology and Immunology, 2002. 190(4): p. 153-160.

3. Korr, G., et al., Decreasing seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 in Germany leaves many people susceptible to genital infection: time to raise awareness and enhance control. BMC Infectious Diseases, 2017. 17(1): p. 471.

4. Roizman, B., D.M. Knipe, and R.J. Whitley, Herpes Simplex Viruses, in Fields Virology, D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley, Editors. 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

5. AWMF, Virale Meningoenzephalitis − Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie, in Register-Nr.: 030/10. 2018.

6. Cohen, J.I., S.E. Strauss, and A.M. Arvin, Varicella-Zoster Virus Replication, Pathogenesis, and Management, in Fields Virology, D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley, Editors. 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

7. Gershon, A.A., et al., Varicella zoster virus infection. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2015. 1(1): p. 15016.

8. Katz, J. and R. Melzack, Measurement of pain. The Surgical Clinics of North America, 1999. 79(2): p. 231-252.

9. AWMF, SK-2-Leitlinie Diagnostik und Therapie des Zoster und der Postzosterneuralgie, in Register-Nr.: 013-023, AWMF, Editor. 2019.

10. Curhan, S.G., et al., Herpes Zoster and Long‐Term Risk of Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of the American Heart Association, 2022. 11(23): p. e027451.

11. Elhalag, R.H., et al., Herpes Zoster virus infection and the risk of developing dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore), 2023. 102(43): p. e34503.

12. Shah, S., et al., Herpes zoster vaccination and the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav, 2024. 14(2): p. e3415.

13. Taquet, M., et al., The recombinant shingles vaccine is associated with lower risk of dementia. Nat Med, 2024. 30(10): p. 2777-2781.

14. Xie, M., et al., The effect of herpes zoster vaccination at different stages of the disease course of dementia: Two quasi-randomized studies. medRxiv, 2024.

15. Schmidt, S.A.J., et al., Incident Herpes Zoster and Risk of Dementia: A Population-Based Danish Cohort Study. Neurology, 2022. 99(7): p. e660-e668.

16. Levine, K.S., et al., Virus exposure and neurodegenerative disease risk across national biobanks. Neuron, 2023. 111(7): p. 1086-1093.e2.

17. Robert-Koch-Institut, Epidemiologisches Bulletin 04/2022. 2022.

18. GlaxoSmithKline, Fachinformation Herpes zoster-Totimpfstoff. 2023.

19. Martro, E., et al., Comparison of human herpesvirus 8 and Epstein-Barr virus seropositivity among children in areas endemic and non-endemic for Kaposi's sarcoma. Journal of Medical Virology, 2004. 72(1): p. 126-131.

20. Dunmire, S.K., P.S. Verghese, and H.H. Balfour, Primary Epstein-Barr virus infection. Journal of Clinical Virology, 2018. 102: p. 84-92.

21. Vine, L., et al., P19 Symptomatic Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) Hepatitis is uncommon, but occurs in patients of any age, including the elderly. Gut, 2011. 60(2): p. A9.

22. Watanabe, M., et al., Acute Epstein-Barr related myocarditis: An unusual but life-threatening disease in an immunocompetent patient. Journal of Cardiology Cases, 2020. 21(4): p. 137-140.

23. Accomando, S., et al., Epstein-Barr virus-associated acute pancreatitis: a clinical report and review of literature. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 2022. 48(1): p. 160.

24. Niazi, M.R., et al., Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) induced pneumonitis in an immunocompetent adult: A case report. Respiratory Medicine Case Reports, 2020. 31: p. 101262.

25. Rickinson, A.B. and E. Kieff, Epstein-Barr Virus, in Fields Virology, D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley, Editors. 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

26. Wong, Y., et al., Estimating the global burden of Epstein-Barr virus-related cancers. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 2022. 148(1): p. 31-46.

27. Scheibenbogen, C., et al., Chronisches Fatigue-Syndrom: Heutige Vorstellung Zur Pathogenese, Diagnostik Und Therapie. Tagliche Prax, 2014.

28. Loebel, M., et al., Deficient EBV-Specific B- and T-Cell Response in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. PLOS ONE, 2014. 9(1): p. e85387.

29. Bjornevik, K., et al., Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science (New York, N.Y.), 2022. 375(6578): p. 296-301.

30. Lanz, T.V., et al., Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature, 2022. 603(7900): p. 321-327.

31. Vietzen, H., et al., Accumulation of Epstein-Barr virus–induced cross-reactive immune responses is associated with multiple sclerosis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2024. 134(21).

32. Soldan, S.S. and P.M. Lieberman, Epstein–Barr virus and multiple sclerosis. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2022: p. 1-14.

33. Dobson, R., et al., Epstein-Barr–negative MS: a true phenomenon? Neurology - Neuroimmunology Neuroinflammation, 2017. 4(2): p. e318.

34. Sokal, E.M., et al., Recombinant gp350 Vaccine for Infectious Mononucleosis: A Phase 2, Randomized, Double- Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Safety, Immunogenicity, and Efficacy of an Epstein- Barr Virus Vaccine in Healthy Young Adults. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2007. 196(12): p. 1749-1753.

35. https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

36. Cohen, J.I., Therapeutic vaccines for herpesviruses. J Clin Invest, 2024. 134(9).

37. Zhong, L., et al., Prophylactic vaccines against Epstein–Barr virus. The Lancet, 2024. 404(10455): p. 845.

38. Jr., E.S.M., T. Shenk, and R.F. Pass, Cytomegaloviruses, in Fields Virology, D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley, Editors. 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

39. Marsico, C. and D.W. Kimberlin, Congenital Cytomegalovirus infection: advances and challenges in diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 2017. 43(1): p. 38.

40. Enders, G., et al., Cytomegalovirus (CMV) seroprevalence in pregnant women, bone marrow donors and adolescents in Germany, 1996–2010. Medical Microbiology and Immunology, 2012. 201(3): p. 303-309.

41. Robert-Koch-Institut, RKI-Ratgeber Zytomegalievirus-Infektion. 2018.

42. Barton, M., A.M. Forrester, and J. McDonald, Update on congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Prenatal prevention, newborn diagnosis, and management. Paediatrics & Child Health, 2020. 25(6): p. 395-396.

43. Robert-Koch-Institut. RKI-Ratgeber Zytomegalievirus-Infektion. [cited 2022 2022/12/12]; Available from: https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/Infekt/EpidBull/Merkblaetter/Ratgeber_Zytomegalievirus.html.

44. Mark R. Schleiss, S.A.P., 16 - Cytomegalovirus Vaccines, in Plotkin’s Vaccines, P.A.O. STANLEY A. PLOTKIN, WALTER A. ORENSTEIN, KATHRYN M. EDWARDS, Editor. 2018, Elsevier: Philadelphia.

45. Schleiss, M.R., et al., Proceedings of the Conference “CMV Vaccine Development—How Close Are We?” (27–28 September 2023). Vaccines, 2024. 12(11): p. 1231.

46. https://ictv.global/taxonomy.

47. Agut, H., P. Bonnafous, and A. Gautheret-Dejean, Laboratory and Clinical Aspects of Human Herpesvirus 6 Infections. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2015. 28(2): p. 313-335.

48. Ward, K.N., The natural history and laboratory diagnosis of human herpesviruses-6 and -7 infections in the immunocompetent. Journal of Clinical Virology, 2005. 32(3): p. 183-193.

49. Yamanishi, K., Y. Mori, and P.E. Pellett, Human Herpesviruses 6 and 7, in Fields Virology, D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley, Editors. 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

50. Wiersbitzky, S., et al., [Seroprevalence of antibodies to human herpesvirus 6 (exanthema subitum; critical 3-day fever-exanthema in young children) in the population of Northern Germany]. Kinderarztliche Praxis, 1991. 59(6): p. 170-173.

51. Krueger, G.R.F., et al., Comparison of Seroprevalences of Human Herpesvirus-6 and -7 in Healthy Blood Donors from Nine Countries. Vox Sanguinis, 1998. 75(3): p. 193-197.

52. Ogata, M., et al., Clinical characteristics and outcome of human herpesvirus-6 encephalitis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 2017. 52(11): p. 1563-1570.

53. Flamand, L., Chromosomal Integration by Human Herpesviruses 6A and 6B, in Human Herpesviruses, Y. Kawaguchi, Y. Mori, and H. Kimura, Editors. 2018, Springer Singapore: Singapore. p. 209-226.

54. Nam Leong, H., et al., The prevalence of chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6 genomes in the blood of UK blood donors. Journal of Medical Virology, 2007. 79(1): p. 45-51.

55. Arbuckle, J.H., et al., The latent human herpesvirus-6A genome specifically integrates in telomeres of human chromosomes in vivo and in vitro. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2010. 107(12): p. 5563-5568.

56. Gravel, A., et al., Inherited chromosomally integrated human herpesvirus 6 as a predisposing risk factor for the development of angina pectoris. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015. 112(26): p. 8058-8063.

57. Cesarman, E., et al., Kaposi sarcoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2019. 5(1): p. 1-21.

58. Malope-Kgokong, B.I., et al., Kaposi's Sarcoma Associated-Herpes Virus (KSHV) Seroprevalence in Pregnant Women in South Africa. Infect Agent Cancer, 2010. 5: p. 14.

59. Sung, H., et al., Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2021. 71(3): p. 209-249.

60. Host, K.M., et al., Kaposi's sarcoma in Malawi: a continued problem for HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals. AIDS, 2017. 31(2): p. 318-319.

61. Stoeter, O., et al., Trends in childhood cancer incidence in sub-Saharan Africa: Results from 25 years of cancer registration in Harare (Zimbabwe) and Kyadondo (Uganda). International Journal of Cancer, 2021. 149(5): p. 1002-1012.

62. Lönard, B.M., et al., Estimation of Human Herpesvirus 8 Prevalence in High-Risk Patients by Analysis of Humoral and Cellular Immunity. Transplantation, 2007. 84(1): p. 40-45.

63. Ganem, D., Kaposi's Sarcoma-associated Herpesvirus, in Fields Virology, D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley, Editors. 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia.

Stellen Sie Ihre Frage

- Wir können keine Fragen zu spezifischen Patientenfällen, Produktempfehlungen oder off-label-Themen beantworten.

- Bitte geben Sie so viele Details wie möglich an, damit unsere Experten Ihnen die bestmögliche Antwort geben können. Achten Sie darauf, Ihre Frage klar und präzise zu formulieren.

- Seien Sie klar und spezifisch

- Geben Sie genügend Kontext, damit andere Ihre Frage leicht verstehen können.

- Beispiel: Anstatt "Welche Impfungen braucht man auf Reisen?" fragen Sie lieber "Welche Impfungen werden für eine Reise nach Südostasien empfohlen und was muss man beachten?"

- Halten Sie sich an unsere Richtlinien

- Vermeiden Sie Fragen zu Produkten, spezifischen Patientenfällen sowie off-label-Themen, da wir diese nicht beantworten dürfen.

- Beispiel: Anstatt "Kann ich Patient X Impfstoff Y verabreichen?" fragen Sie lieber "Welche Kontraindikationen muss ich bei einer Impfung gegen Grippe beachten?"

- Überprüfen Sie bestehende Fragen

- Nutzen Sie unsere automatischen Vorschläge bei Texteingabe, um die Doppelung von Fragen zu vermeiden.

Welche Impfungen werden Schwangeren ohne Vorerkrankungen empfohlen?

- Sie ist spezifisch und für ein breites Publikum geeignet.

- Sie vermeidet Fragen zu bestimmten Impfstoffen oder individuellen Patientenfällen.

- Sie konzentriert sich auf offizielle Empfehlungen und nicht auf persönliche Meinungen.

Warum diese Frage geeignet ist:

Oder stellen Sie Ihre Frage auf der Detailseite.

- Tipps für eine gute Frage – So formulieren Sie klar und präzise.

- Beispielfrage – Ein Muster für eine gut strukturierte Anfrage.

Dort finden Sie: